Last year, I learned how to do chromatography. You may be familiar with science class experiments where you apply a ground up plant or a marker to a piece of filter paper and watch as the colors in your sample separate out as capillary action carries them across the paper.

In photography, chromatography is based on the same principles, but the sample is absorbed by paper that’s been coated with silver nitrate. This means that in order to see the final image, the paper must be exposed to UV light.

Chromatography is like taking a photograph of the compounds and microorganisms that make up a substance. It’s more commonly used by farmers who are checking the health of their soil. The more striations and color variations, the more microbial activity in the soil, and the healthier it is.

As plants and fungi grow, they absorb nutrients from soil and host the microorganisms in the area. When you eat, you are, in a sense, eating the soil where the food was grown. Food is never truly divorced from the land that nurtured it.

As an Asian American, it’s easy to feel uprooted. Fellow Americans refuse to see you as American. And people living in the motherland don’t see you as one of theirs either.

China has always loomed large in my thoughts and dreams. It lives in an imaginary space of Pau Pau’s reminisces about what life was like as she grew up during colonization, before the CCP took power. It lives in an imaginary space of the photos and videos I’ve seen online of Chinese cities and villages, as I try to piece together what my family’s villages may have looked like a century ago.

A common view (borne of racism) that the Global North has of the Global South is that the South is unchanging and backward. Growing up in the diaspora and being raised by your grandmother can reinforce the notion that the land is stuck in time because your main references for the country are stories that happened decades before you were born.

When I grew up and first realized that my childish imaginings almost certainly didn’t match up with reality, I felt somewhat unmoored. What would it even mean for me to go to China and see what it’s like? I want to see the places that meant the most to Pau Pau. But are they even standing? Has her childhood home been paved over? Has the creek she waded through dried up? Is the forest she hid in from soldiers still standing?

White Americans- even some of my own family members- have made it clear that I’m not really American. Living in this land and not feeling truly part of it has left me with a hunger for another land.

What a gift it has been to realize that the land of China has been physically nurturing me my entire life. All the imported food I’d help Pau Pau shop for at her favorite Chinatown grocery store, Star Light Market, carried with it traces of the land. Dried orange peels, shiitake mushrooms, lap cheong. All the nutrients absorbed from Chinese soil.

And pu-erh. Pau Pau’s favorite tea.

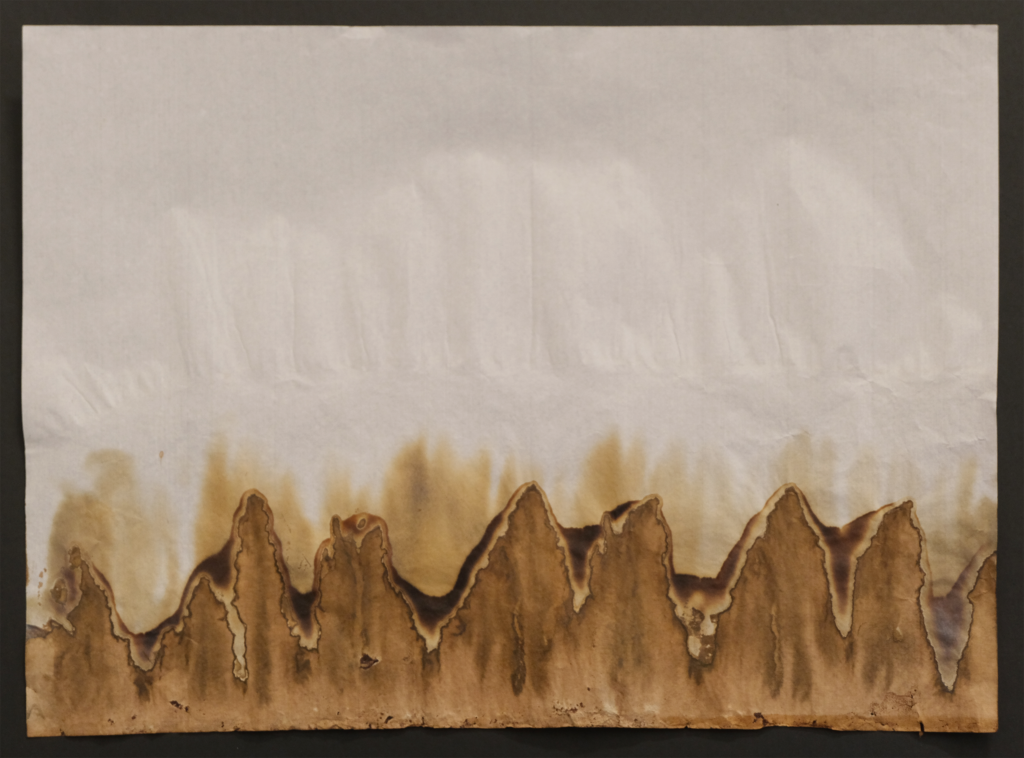

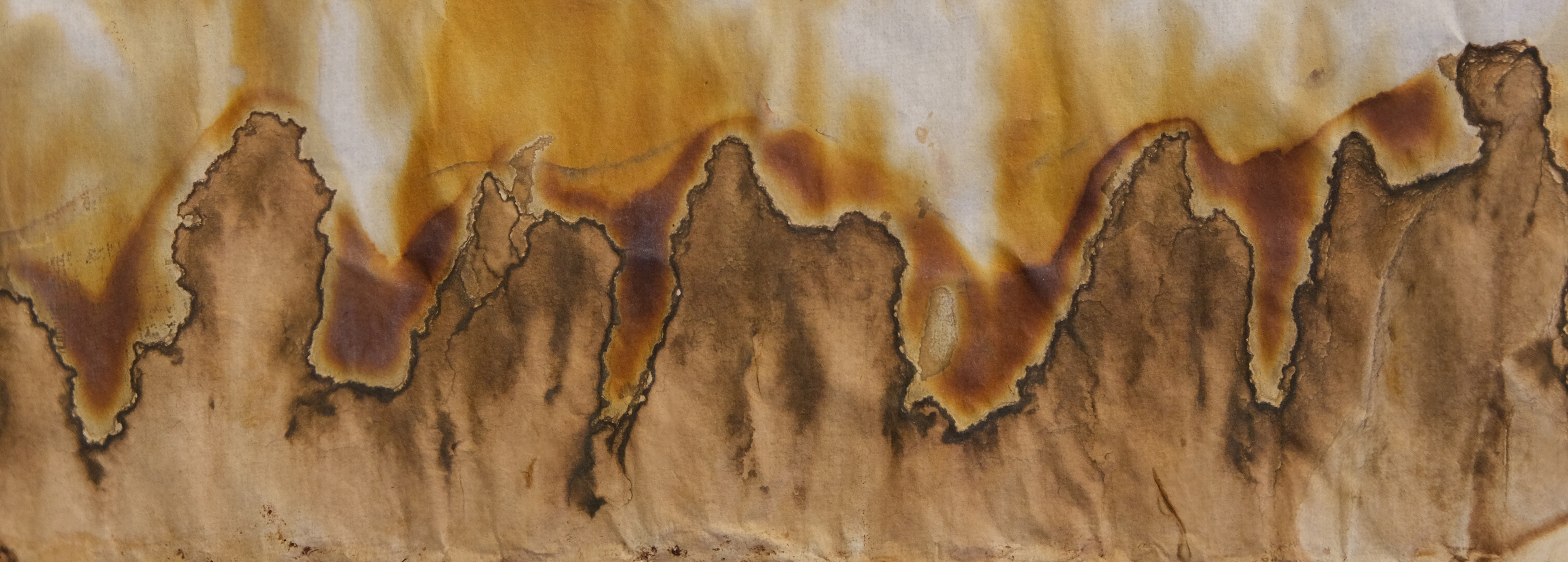

Once I learned chromatography, I was able to visualize the land’s abundance and generosity in ways I hadn’t imagined. And some of my prints even look like mountainous landscapes, reminiscent of the mountains of Hoisan/台山/Taishan, where my ancestors are from.

For me, chromatography is a gift. A visual reminder of the land that I may be separated from but that has always given me love.

The chromatograms in this post are my first prints of pu-erh dragon balls made with oranges grown in Guangdong, the region my family is from. Dragon balls are tiny oranges picked when green, hollowed out, and stuffed with tea.

While Pau Pau likely never had dragon balls because they would have been too expensive for her to afford when she lived in China and Hong Kong, I see this work- me brewing and making images with dragon balls- as the promise she worked her entire adult life for, to give her family a more stable and prosperous life than she had. It is a profound privilege born out of generational trauma. And I feel very fortunate to be able to not just drink her favorite tea, but to enjoy it in ways that she could not.

That is one of the gifts that chromatography has given me; it lets me visualize my family love and history. It shows me not just the land we come from, but a prosperous present and hope for the future.

This is just the beginning of a series of chromatograms of home found in food. Of love, land, and belonging.

Leave a Reply